Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, to bring you to God, by being put to death in the flesh but by being made alive in the spirit. In it he went and preached to the spirits in prison, after they were disobedient long ago when God patiently waited in the days of Noah as an ark was being constructed. (1 Peter 3:18-20)

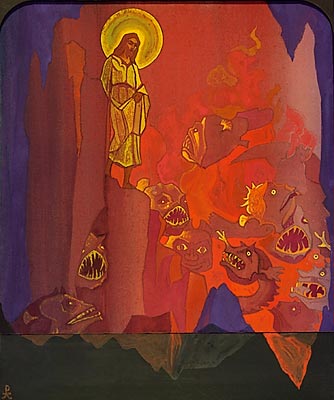

At its core, the doctrine of Christ’s Harrowing of Hell represents a way of interpreting the meaning of Christ’s death and resurrection—a way that stresses the rescue of individuals from the transience of the human condition. By plundering righteous souls imprisoned in the underworld, Christ gives humans throughout time a share in his resurrection life and victory over death. Believers therefore need not succumb to the existential dread brought on by Death’s callous approach.

In this way Christ’s Harrowing of Hell offers answers to some of our most profound questions regarding life and death. The doctrine assures us that death is not final, and reminds believers that they will enjoy unending bodily existence even after life’s end.

Existential or eschatological?

Yet for all the questions it answers, the interpretive lens provided by the doctrine also distorts and mutes the eschatological and political outcomes which early Christians believed the Messiah’s death and resurrection foretold.

The Harrowing of Hell doctrine does this in two ways.

First, it conflates our natural human death with Christ’s death as a martyr. Christ and his followers died not as those unfortunately bound by the human condition, but as God’s saints persecuted by the ungodly on account of their prophetic message (cf. Daniel 7:21-22). When the early Christians spoke of Death as their enemy, they were primarily referring to the fate of those suffering the politically-motivated torment brought on by eschatological tribulations.

Second, the Harrowing of Hell presents Christ’s resurrection as an event of existential significance rather than apocalyptic significance. For the first believers, Christ’s transformation through death signaled not the defeat of death in some abstract sense, but the nearness of the resurrection of all the dead at the end of the age. Christ was the first-fruits of the resurrection because the whole tree was about to ripen. The concern was therefore not How do I escape my human frailty? but How can our God allow the righteous to be slaughtered and laid in the dirt? As Paul complains in Romans 8:

Who will separate us from the love of Christ? Will hardship, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? As it is written, ‘For your sake we are being killed all day long; we are accounted as sheep to be slaughtered.’

Paul’s concern was not the hardships associated with natural human life, but the specific realities incumbent upon his churches as they existed at the margins of a hostile pagan world. Christ’s resurrection meant Christian martyrs would be vindicated on account of their faithful suffering over and against their enemies (cf. Phil 3:10-11).

Thus what appears to us to be existential, even psychological, in scope was for the first Christians eschatological and political.

Enoch and the captive angels

Enoch and the captive angels

In light of these short-comings I’d like to offer an alternative reading of 1 Peter 3:18-20 and Christ’s infernal descent.

In his IVP NT Background Commentary Craig Keener outlines what is now a popular view among scholars: that the Enochic myth of the fallen angels lies behind 1 Peter 3:18-20 (718). According to this legend, during the days of Noah those angelic spirits who rebelled against God, mated with human women, produced depraved progeny, and taught humanity the arts of wickedness, were imprisoned in the underworld in order to await their final punishment at the eschaton (cf. 1 Enoch 10:15-16, 18:11-16, 21:6, 54:5, Jubilees 5:6-7).

Early Christians, for their part, exhibit some interest in 1 Enoch as well as in this myth of angelic captivity—sometimes using it as an example of God’s justice.

For if God did not spare angels when they sinned, but cast them into Tartarus and committed them to chains of gloomy darkness to be kept until the judgment; and if he did not spare the ancient world, even though he saved Noah… (2 Peter 2:4-5)

And the angels who did not keep their own position, but left their proper dwelling, [God] has kept in eternal chains in deepest darkness for the judgment of the great day. (Jude 6)

What this means for 1 Peter 3:18-20 is that the “imprisoned spirits” to whom Christ “preached” were probably not human souls (though the Enochic literature does place the particularly wicked in the netherworld as well), but rather the rebellious angels of Noah’s age, those spirits bound in the heart of the earth until the time of their punishment.

Christ’s descent would then parallel Enoch’s own otherworldly evangelistic journeys:

Then the Lord said to me: ‘Enoch… go tell the Watchers of heaven, who have deserted the lofty sky, and their holy everlasting station, who have been polluted with women… That on the earth they shall never obtain peace and remission of sin. For they shall not rejoice in their offspring; they shall behold the slaughter of their beloved; shall lament for the destruction of their sons; and shall petition for ever; but shall not obtain mercy and peace. (1 Enoch 12:5-7, cf. 17:1-19:3, 22:1-15)

With this story in view, Peter presents Christ, like Enoch, proclaiming the decree of eschatological judgement over the imprisoned spirits. According to Christ’s underworld kerygma, evil spirits will not escape their chains or their destiny (cf. 2 Peter 2:4-5). Hell will not be harrowed, but rather locked up until the day of its destruction (cf. Revelation 1:18).

Why Christ descended: the coming flood

There are a couple of reasons early Christians might have been interested in a story about Christ journeying within the gates of Hades.

- The gospel of the kingdom had to be announced throughout all creation in order for the eschaton to advance (cf. Col 2:23, 1 Thess 1:8, 1 Tim 3:16). That Christ had accomplished the task in Tartarus meant that the end was very near. Soon every knee, even those knees imprisoned under the earth, would bend to Christ and his God (Phil 2:10). God’s kingdom and God’s judgement would invade every corner of the cosmos.

- The announcement of impending punishment over captive spirits implied that their earthly tributaries were about to be dismantled. As symbolized by Christian baptism, an apocalyptic flood would soon be unleashed upon the earth to destroy evildoers. Along with their spiritual patrons, idolatrous rulers and their nations would be judged and destroyed (Revelation 19:11-21). On that day the Lord would punish “the host of heaven, and on the earth the kings of the earth” (Isaiah 24:21-22).

Beyond these motivations, Jesus’ exorcistic ministry may have also given rise to speculation. During Jesus’ life demons had fled from him in terror, apparently frightened that the eschatological judgement had come “before the appointed time” (πρὸ καιροῦ) (Matthew 8:29); that God’s son had arrived early to “destroy” them (Mark 1:24). Given the eschatological schedule in place, unclean spirits wondered what business Christ had with them (τί ἐμοὶ καὶ σοί) (Luke 8:28). Was it an ambush?

Christ, so it seems, had not come to execute God’s judgement, but to announce it in advance through the practice of exorcism (cf. Matthew 10:7-8, Mark 6:12-12, Luke 11:20). As he fulfilled this prophetic task among the spirits on earth, so he did also among the spirits under the earth. Christ’s descent into Hell was therefore a logical extension of his exorcistic ministry.

Great summary of the 1 Peter passage! You’ve explained some very complex background really well.

LikeLiked by 1 person